In a 2013 interview, Verne Harris, Director of Research at the Nelson Mandela Centre for Memory, reflected on the construction of Madiba’s legacy(ies). “No legacy is simply received,” he noted, “every legacy is always made and remade.” This making and remaking of Mandela’s legacy has come into sharp focus in the past few months as the world reeled from the loss of this iconic leader. The obituaries that proliferated following his passing bring this myth-making into stark focus. In a previous post for this blog, I cited Mark Gevisser’s obituary of Madiba which was posted to the Mail & Guardian website almost immediately after his death was confirmed. In this piece, Gevisser wrote that Mandela appealed to so many people because

In a 2013 interview, Verne Harris, Director of Research at the Nelson Mandela Centre for Memory, reflected on the construction of Madiba’s legacy(ies). “No legacy is simply received,” he noted, “every legacy is always made and remade.” This making and remaking of Mandela’s legacy has come into sharp focus in the past few months as the world reeled from the loss of this iconic leader. The obituaries that proliferated following his passing bring this myth-making into stark focus. In a previous post for this blog, I cited Mark Gevisser’s obituary of Madiba which was posted to the Mail & Guardian website almost immediately after his death was confirmed. In this piece, Gevisser wrote that Mandela appealed to so many people because

Mandela epitomised those instincts we most associate with childhood: trust, goodness, optimism; an ability to vanquish the night’s demons with the knowledge that the sun will rise in the morning. But he also made us feel good, and warm, and safe, because he found a way to play an ideal father, beyond the confines of his biological family or even his national one. He was the father we would all have wanted if we could have designed one. He was wise with age, benignly powerful, comfortingly irascible, stern when we needed containing, breathtakingly courageous, affirming when we needed praise – and, of course, possessed of the two childlike qualities that make for the best of fathers: an exhilarating playfulness and a bottomless capacity to forgive.

While this characterization is, no doubt, true in some measure, this portrait of Madiba falls into the mythology of Mandela pointed out in Benjamin Fogel’s 2013 article in The Jacobin.

There were really two Mandelas. The first is that of the revolutionary, the lawyer, the politician, flaws and all. The second is a sanitized myth: the father of the nation, the global icon beloved by everyone from the purveyors of global humanitarian platitudes to even the erstwhile enemies of the African National Congress. This Mandela is removed of his humanity and touted as an abstract signifier of moral righteousness.

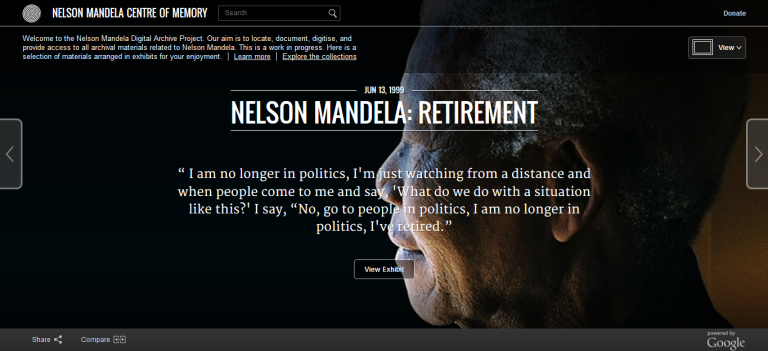

With this perspective, the portrait painted by Gevisser is laid bare as myth-making of its own kind; perpetuating the myth of Mandela, as Fogel points out, “the benevolent grandfather presented in his post-apartheid representations.” Now, on a popular level, these characterizations of Mandela are powerful, drawing attention to the lifework of a man who did, indeed, sacrifice much of his life for the struggle. The challenge for historians, then, comes in, as Charl Blignaut charged in his article in The City Press, “drawing meaning-and not just commodity-from the legacy that is now entrenched in the pop culture firmament.” One institution which has endeavored to aid in deconstructing Madiba’s legacy is the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory. Founded in 2004, in correlation with the Nelson Mandela Foundation, this organization aimed to “create a public facility to deliver to the world an integrated and dynamic information resource on his life and times, and promote the finding of sustainable solutions to critical social issues, through memory based dialogue interventions.” These aims were furthered in 2011 when the Centre of Memory partnered with the Google Cultural Institute to launch a digital archive.

Arranged along a series of chronological snippets of Madiba’s life, each virtual exhibits presents rich textual descriptions of certain episodes in Mandela’s life, enriched by primary sources, including textual and multimedia sources, that correlate with those chronological spans. Though the site is, without a doubt, incomplete, with large gaps in content for Madiba’s early involvement with politics to his imprisonment, it is an easily navigable and digestable interface. The design is coherent through each of the various sections, allowing the primary sources to be highlighted, providing relevant content while also leaving room for the audience to explore the site more fully through the somewhat hidden digital archive.

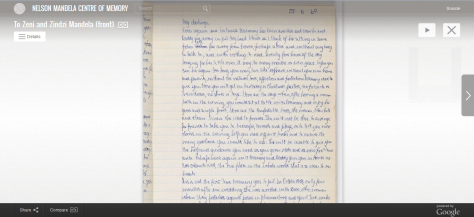

The striking thing about the Mandela Centre of Memory is the rich digital archive that it is built on, featuring many historical documents and media that have not yet been incorporated into the storytelling component of the site. In particular, the never-before-published draft of Long Walk to Freedom is available through the archive, providing an inside look into how Mandela (and his co-writer Richard Stengel) viewed himself, especially during his presidential term which, as Fogel suggested, “is glossed over as some sort of miracle period in which he was able to unite black and white; his own political successes and failures in his one and only term go unexamined.” Similarly, the inclusion of a number of Mandela’s journals from his time in prison, allow for the user to, in Verne Harris’ words, “get in behind that [Madiba’s public image], unguarded. This what Madiba says to himself. This is what he notes down as he sees, as he experiences.” Reading these entries, some of which have been previously published in Conversations with Myself or A Prisoner in the Garden, helps to get to the core of not only what life was like for Madiba in these trying times, but also, in a way, how he viewed himself.

Comparatively, PBS’ The Long Walk of Nelson Mandela is built not on multimedia sources, but rather on the oral testimonies of close friends and comrades of Mandela. Featuring interviews from some icons of the struggle against apartheid (I was quite excited to see Govan Mbeki included) , this site compiles a rich array of oral sources on not only Madiba, but also the struggle against apartheid more broadly. Chris Saunders noted the great potential of oral histories to correct the gaps in the archives of liberation history; those interviews collected here can be added to the list of digitally accessible oral testimonies already in circulation (including those contained in MSU’s own Overcoming Apartheid and CVET collections). However, it is unfortunate that the interviewers decided to transcribe the interviews rather than preserve their testimonies in audio or video formats. The Google site is greatly enhanced by the inclusion of videos featuring Madiba’s own voice.

Comparatively, PBS’ The Long Walk of Nelson Mandela is built not on multimedia sources, but rather on the oral testimonies of close friends and comrades of Mandela. Featuring interviews from some icons of the struggle against apartheid (I was quite excited to see Govan Mbeki included) , this site compiles a rich array of oral sources on not only Madiba, but also the struggle against apartheid more broadly. Chris Saunders noted the great potential of oral histories to correct the gaps in the archives of liberation history; those interviews collected here can be added to the list of digitally accessible oral testimonies already in circulation (including those contained in MSU’s own Overcoming Apartheid and CVET collections). However, it is unfortunate that the interviewers decided to transcribe the interviews rather than preserve their testimonies in audio or video formats. The Google site is greatly enhanced by the inclusion of videos featuring Madiba’s own voice.

One particularly interesting element of the site that integrates audio and video in compelling ways, from a public history perspective, is the section entitled “My Moment With A Legend.” The inclusion of this series of videos and photos with individuals’ reflections of their encounters with Madiba speaks to the public role of the Centre of Memory; a recognition that, as Verne Harris has explained,

a legacy cannot belong to one institution, to one family, to one country…the legacy belongs to all of us and it only has life, it only has meaning if we are interrogating it, if we are interpreting it….the role is to create space for people to engage with that legacy and in that process to remake it.

This site certainly succeeds in creating this space; it would be interesting to see them add a component to this site for the postmortem reflections of how the public consumed and experienced this icon’s passing. Thinking about how these vignettes engage with the user’s senses on various levels (reading text, hearing testimony, at times from Mandela himself, seeing images), the power of the digital face of this site becomes apparent. Integrating scholarly analysis (though geared for a lay audience) which rich supporting evidence, this site does allow for users to explore Mandela’s legacy in their own way. However, this site may not be particularly geared for critical engagement with the legacy of this icon. Given the large gaps in chronology, somewhat conveniently hopping around the moments at which Mandela’s image because the most difficult to pin down, the Mandela that is presented is fairly simple, uncomplicated by his faults or his complexities. That being said, the digital archive does not suffer from these same gaps; once a user accesses the archive itself they can explore the sources however they choose.

This site, then, holds the capacity to aid historians and other interested parties in move past, in Fogel’s words, “analyzing Mandela not as the person he was, but through the lens of the mythology surrounding him-operating in the symbolic rather than historical realm,” allowing for the public to imbibe Madiba through the frontward facing component of the site and scholars to critically investigate and craft Madiba’s legacy in the digital archive that forms its foundation. It will be interesting to see how the archive develops now, in the wake of Madiba’s passing; will it fill in those chronological gaps? Add more content to further complicate Madiba’s legacy? Incorporate more voices from the public? In this way, this site as it stands now, has to be seen as a work in progress which holds great potential for presenting and preserving the history of one of South Africa’s greatest leaders, no matter which myth the viewer ascribes to.

This post is one of the requirements for South African History in a Digital Age, a graduate course in history which I am enrolled in this semester, drawing on the assigned readings for January 30.

I agree with your assessment of the site. I think it’s a wonderful product, that has plenty of room to improve. The memory of Mandela as a historical figure belongs to the public in a way that few others do. It is easy to use, and contains a lot of really fascinating content, especially if you strike out on your own.

I’m curious what kinds of content you would add? Would you like to fill in some personal gaps, or gaps in his work as an activist, revolutionary, and statesman? I don’t know enough about Mandela to pinpoint areas that are definitely lacking. What do you think?

There are a lot of gaps that I would fill in. If you read Mandela’s writing over the longue duree of his political career, you really see him change in terms of his political leanings. He was, truly, a revolutionary, attracted to socialism and communism in real ways: he had a dog named Kruschev (did you know that?) I think that a vignette on his development as a political figure would be really interesting and would problematize the public perception of him as a “saint.” There are lots of others, but that’s the first one that I would address. There’s so much room to make this a rich resource for picking apart his public image.

I agree with you that more on his early politics would be a very interesting addition that would challenge the way most people’s public perception. I was wondering if you felt that the PBS site was in a way also creating an image of Mandela that reflected things that were already in hist autobiography and were therefor an official narrative?

Well, I feel like there are multiple layers to the official narrative, as Mandela has published many different works that all contribute to an overall narrative. But he is not overly generous with himself in a lot of cases. When you read his autobiography (and perhaps even more in Conversations with Myself) his internal conflicts are quite visible. I don’t know that the PBS site is part of an official narrative–it’s hard to know without seeing the interviews. Was Carlin leading the interviewees with questions? Were they given a kind of doctrine of what kind of documentary FRONTLINE wanted before they started? These things are always difficult to know without being there.